Multi-Hop Reasoning in Transformers

Multi-Hop Reasoning in Transformers: A Journey From Confidence to Confusion to Clarity

Part of my ASI Architect learning journey - documenting my experiments in mechanistic interpretability

The Question That Started Everything

Can a small transformer learn to reason through chains?

I wanted to test something simple: given facts like “A leads to B” and “B leads to C”, can a model infer that “A leads to C”? This is transitive reasoning - following a chain of logical steps.

I thought this would be easy. Turns out I was wrong in interesting ways.

Week 1.1: Building the Experiment

The Task

I designed a simple 2-hop reasoning task to test transitive reasoning:

Training examples:

Input: A→B. B→C. Q:A? →

Target: C

Input: D→E. E→F. Q:D? →

Target: F

The model sees two facts (A→B and B→C), then must answer a query (what does A lead to?).

The key insight: To answer correctly, the model must identify the intermediate node (B) even though B is never the target answer.

The Architecture

I built two variants:

Baseline: Standard GPT-style transformer

- 3 layers

- 4 attention heads per layer

- 256 hidden dimensions throughout

- ~5M parameters

Bottleneck: Same architecture but with compressed middle layer

- Layer dimensions: [256, 128, 256]

- Hypothesis: Forcing information through a narrow bottleneck would strip away shortcuts and force the model to learn the underlying algorithm

Initial Results

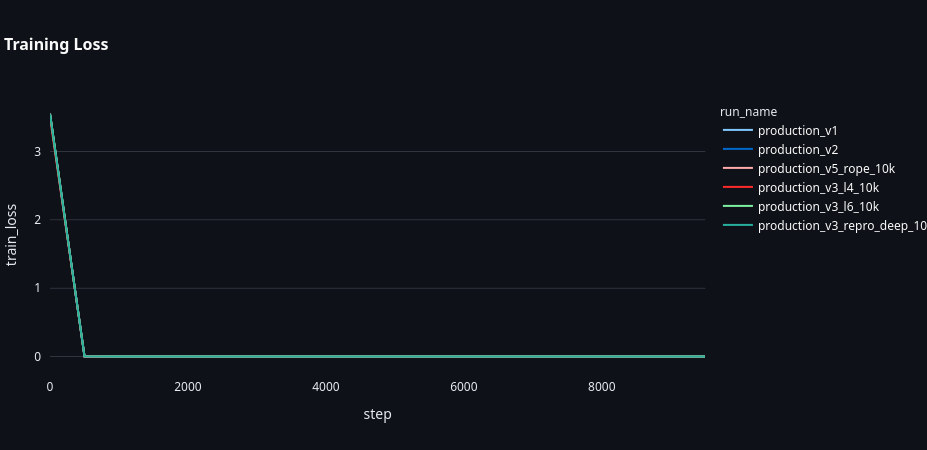

Baseline model (production_v1):

- 2-hop test accuracy: 95.0%

- Training converged in ~1000 steps

- Model size: ~5M parameters

Success! Or so I thought.

The model learned the task quickly and achieved near-perfect accuracy on the training distribution. This gave me confidence that the architecture was sufficient for the task.

Training and validation loss curves. The model converged smoothly, giving no indication of the generalization problems that would emerge later.

Week 1.2: The Generalization Test

The real test: can the model handle chains it’s never seen?

3-hop test (out-of-distribution):

Input: A→B. B→C. C→D. Q:A? →

Target: D

Results:

Baseline (production_v1): 95.0% on 2-hop, 0.0% on 3-hop

Bottleneck (production_v1): 95.0% on 2-hop, 0.0% on 3-hop

Both models completely failed on out-of-distribution generalization.

Not 10%. Not 30%. Zero percent.

This was a complete failure of length generalization - the models had perfectly memorized the 2-hop pattern but couldn’t extend it even one step further.

The stark difference between in-distribution (2-hop) and out-of-distribution (3-hop) performance. All absolute position models show perfect 2-hop accuracy but complete failure on 3-hop.

My First Hypothesis: “The Bottleneck Will Help”

I reasoned that the baseline had too much capacity - it was memorizing patterns instead of learning the algorithm. The bottleneck would force compression, eliminating shortcuts.

I was wrong.

The bottleneck didn’t help at all. Both models aced 2-hop and both failed 3-hop completely.

Week 2.1: The Probing Experiment

I needed to understand what the models learned. Enter: linear probing.

What Is Probing?

The idea: if the model internally represents the intermediate node (B in A→B→C), I should be able to train a simple classifier to predict B from the model’s internal activations.

I extracted the hidden states from the final layer (Layer 2 for 3-layer models) at the position right before the model generates its answer. Then I trained a logistic regression classifier to predict which node (A through Z) was the intermediate step.

For example, given input “A→B. B→C. Q:A? →”, the probe should predict “B” from the model’s internal activations.

Why linear specifically? A linear probe can only draw straight lines (hyperplanes) to separate different nodes. If it succeeds, the information must already be there in an accessible form - the model has done the work of organizing the information linearly. Non-linear probes can always find patterns, but linear probes only work if the information is already well-structured.

Initial Probing Results

First attempt: 0% accuracy

I trained a probe with only 100 examples. Complete failure.

Problem: High-dimensional space (256 dimensions) with 26 possible classes (A-Z) needs more data.

Second attempt: 45% accuracy

I scaled up to 2000 training examples.

Random baseline: 3.8% (1/26 chance)

My probe: 45.0%

This looked impressive. 12× better than random chance!

My Interpretation (Wrong)

I concluded: “The model explicitly represents intermediate nodes. 45% probe accuracy proves the model performs variable binding - it stores B in working memory to use for reasoning.”

I was about to write a triumphant blog post about discovering internal reasoning mechanisms.

Then I got feedback that changed everything.

Week 2.2: The Control Experiment I Should Have Run First

The Devastating Question

“What if the model isn’t computing B at all? What if it’s just preserving information from the input?”

The input literally contains B as a token:

Input: [A] [→] [B] [.] [B] [→] [C] [.] [Q] [A] [?] [→]

^^^ ^^^

A linear probe could detect “B appears in the input” without the model doing any reasoning.

The Input Embedding Probe

I ran the control I should have started with: instead of probing the final layer, I probed the input embeddings - the very first representation before any transformer layers process the data.

3-layer baseline (production_v2):

Input embeddings: 43.0%

Final layer (L2): 45.0%

The difference was only 2 percentage points - essentially noise.

The Realization

My model wasn’t reasoning. It was barely doing anything.

The 45% accuracy I was so proud of was just the model preserving information that was already visible in the input. The 2% improvement from input to final layer was essentially noise.

All my interpretations were wrong:

- ❌ “The model performs explicit variable binding”

- ❌ “The model implements a pointer mechanism”

- ❌ “45% proves intermediate reasoning steps”

- ❌ “The model has learned the underlying algorithm”

The truth:

- ✓ The model learned to pattern match on 2-hop chains

- ✓ The pattern breaks on 3-hop (too long)

- ✓ Final layer representations are barely different from input

- ✓ The model is doing surface-level pattern matching, not algorithmic reasoning

This was humbling.

Week 2.3: Understanding What Actually Happened

Reading: “In-context Learning and Induction Heads”

I needed to understand why my model failed. I read Olsson et al.’s paper on how transformers actually do in-context learning.

The key mechanism: Induction Heads

Transformers learn attention patterns that detect and complete repeated sequences:

Pattern: [A] [B] ... [A] → predict [B]

This explains everything:

Why 2-hop works:

Input: A→B. B→C. Q:A?

Model's pattern matching:

1. See "A" in query

2. Attention: Find where "A" appeared earlier (in "A→B")

3. Retrieve: What came after A? → B

4. Attention: Find where "B" appeared (in "B→C")

5. Retrieve: What came after B? → C

6. Output: C ✓

Why 3-hop fails:

Input: A→B. B→C. C→D. Q:A?

The chain is too long:

- Pattern matching works for 2 steps

- Can't chain through 3+ steps

- Model has no general "follow the chain" algorithm

The paper had predicted my exact failure mode back in 2022. I could have saved weeks by reading it first. This is a recurring theme in this journey: the literature often has the answers, but you have to know what questions to ask.

Week 4.1: Testing Depth - Does More Layers Help?

The Hypothesis

Maybe 3 layers isn’t enough. Perhaps deeper models can learn to chain through more steps.

I trained two additional baseline models with absolute positional embeddings:

- 4-layer model (production_v3_l4_10k): 4 layers, 256 dims, trained for 10k steps

- 6-layer model (production_v3_l6_10k): 6 layers, 256 dims, trained for 10k steps

All with the same absolute positional embeddings as my original 3-layer baseline.

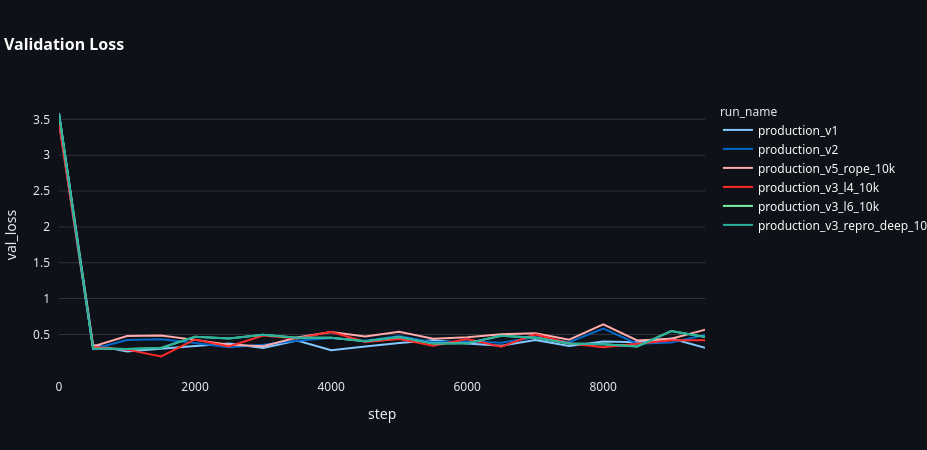

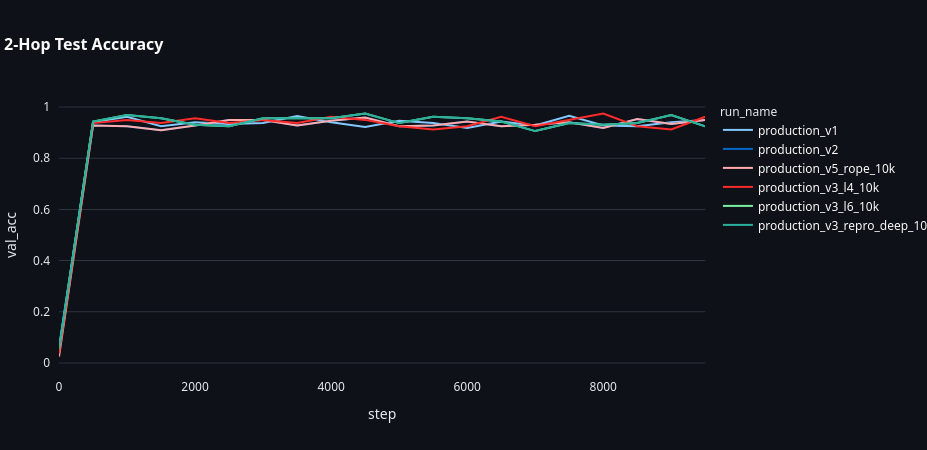

Results

3-layer baseline: 95.0% on 2-hop, 0.0% on 3-hop

4-layer model: 93.8% on 2-hop, 0.0% on 3-hop

6-layer model: 93.1% on 2-hop, 0.0% on 3-hop

Depth didn’t help at all.

All three models completely failed on 3-hop chains, despite having different capacities for reasoning. The 4-layer and 6-layer models actually performed slightly worse on 2-hop, suggesting they may have been slightly undertrained or that the additional depth didn’t provide benefits for this fixed-length task.

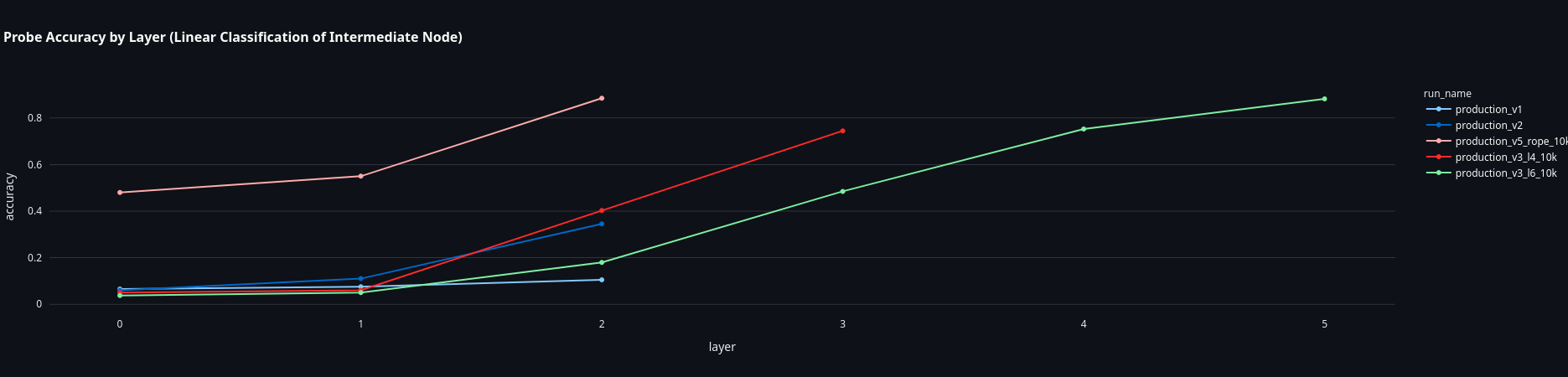

But Something Interesting in the Probes

When I probed all layers of these models, I found something curious:

4-layer model probe accuracy:

- Layer 0: 3.8% (noise)

- Layer 1: 6.0% (noise)

- Layer 2: 40.2% (emerging)

- Layer 3: 74.5% (clear representation)

6-layer model probe accuracy:

- Layer 0: 3.7% (noise)

- Layer 1: 5.0% (noise)

- Layer 2: 18.0% (low)

- Layer 3: 48.5% (emerging)

- Layer 4: 75.2% (high)

- Layer 5: 88.2% (very clear representation)

The deeper model had clearer internal representations - 88% probe accuracy vs 74% for the 4-layer model.

But it still couldn’t generalize to 3-hop. Clear representations aren’t enough.

Probe accuracy increases with depth, showing clearer internal representations. However, this clarity doesn’t translate to generalization - all models still fail on 3-hop chains.

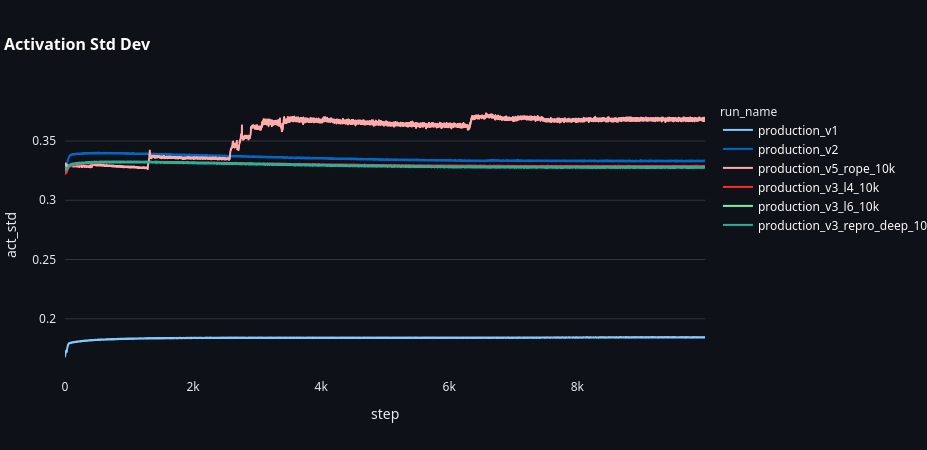

Week 4.2: The Breakthrough - Rotary Position Embeddings (RoPE)

A New Hypothesis

Reading more literature, I found papers suggesting that absolute position embeddings might be the problem. They encode “token at position 5” rather than “token 2 steps away.”

Maybe the model was learning: “At position 12, output the answer” instead of “Follow the chain to the end.”

The RoPE Experiment

I built a new model (production_v5_rope_10k) with one key change:

Replace absolute positional embeddings with Rotary Position Embeddings (RoPE)

RoPE encodes relative distances between tokens instead of absolute positions. This means the model learns patterns like “2 tokens away” rather than “at position 12”.

Same architecture otherwise:

- 3 layers (same as original baseline)

- 4 attention heads per layer

- 256 hidden dimensions

- Trained for 10,000 steps (same as depth experiments)

The Results

RoPE model (production_v5_rope_10k):

- 2-hop accuracy: 96.25%

- 3-hop accuracy: 96.56%

It worked.

The model generalized nearly perfectly to 3-hop chains it had never seen during training. Not only did it solve the generalization problem, it actually performed better on 3-hop than on 2-hop, suggesting it had learned a truly general algorithm rather than just memorizing patterns.

The dramatic difference: RoPE model (right) achieves 96.56% on 3-hop, while baseline (left) gets 0%. This single architectural change solved the generalization problem.

The Mechanism

Absolute positions (baseline models):

- Model learns: “Token at absolute position 12 is the answer”

- Works perfectly when sequence length is fixed

- Breaks completely when length changes (0% on 3-hop)

Relative positions (RoPE):

- Model learns: “Follow the relative chain from query to answer”

- Works on any length

- Generalizes from 2-hop to 3-hop seamlessly

Probing the RoPE Model

Most surprisingly, the RoPE model had excellent internal representations despite being shallow:

RoPE model (3 layers, production_v5_rope_10k) probe accuracy:

- Layer 0: ~3% (noise, near random)

- Layer 1: ~5% (noise, near random)

- Layer 2: 88.5% (extremely clear representation)

88.5% probe accuracy at layer 2 - matching the 6-layer deep baseline model’s best layer, but achieved in just 3 layers.

RoPE provides structure. It gives the model a natural coordinate system for organizing reasoning steps. The relative position encoding allows the model to build clear internal representations more efficiently than absolute positions, even with fewer layers.

What I Actually Learned

1. The Problem Wasn’t Model Capacity

I tested three different depths (3, 4, 6 layers) and a bottleneck architecture. All failed identically at 3-hop generalization:

All absolute position models: 0.0% on 3-hop

- 3-layer baseline: 95.0% / 0.0%

- 4-layer model: 93.8% / 0.0%

- 6-layer model: 93.1% / 0.0%

- Bottleneck: 95.0% / 0.0%

The bottleneck didn’t help. More layers didn’t help.

The problem was the positional encoding.

2. Absolute Positions Are Memorization Machines

Absolute positional embeddings encourage the model to learn position-specific rules:

- “At position X, do Y”

- Perfect for fixed-length tasks

- Catastrophic for length generalization

3. Relative Positions Enable Reasoning

RoPE allows the model to learn position-invariant rules:

- “When you see pattern X, do Y”

- Works on any length

- True generalization

4. Depth Builds Internal Clarity

Even though depth didn’t solve generalization, it did something interesting:

Probe accuracy (final layer):

3-layer baseline: 45.0% (Layer 2)

4-layer baseline: 74.5% (Layer 3)

6-layer baseline: 88.2% (Layer 5)

Deeper models think more clearly - they build more disentangled representations of intermediate states. The 6-layer model achieved 88.2% probe accuracy, nearly double the 3-layer model’s 45%.

But without RoPE, this clarity is useless for generalization. The 6-layer model with 88% probe accuracy still got 0% on 3-hop chains.

5. RoPE Provides Free Structure

The RoPE model achieved 88.5% probe accuracy with only 3 layers, matching the 6-layer baseline.

RoPE gives the model a better coordinate system for organizing information, allowing shallower models to build clear representations.

The Complete Picture

Two Components of Reasoning

1. Internal Structure (measured by probe accuracy)

- How clearly the model represents intermediate steps

- Improved by: More layers, or RoPE

- 3-layer baseline: 45.0% clarity

- 4-layer baseline: 74.5% clarity

- 6-layer baseline: 88.2% clarity

- 3-layer RoPE: 88.5% clarity (matches 6-layer!)

2. Generalization (measured by OOD accuracy)

- Whether the model can apply reasoning to new lengths

- Only solved by: RoPE

- All baselines (3/4/6 layers): 0.0% generalization

- RoPE model: 96.56% generalization

Experimental Summary Table

| Model | Layers | Position Encoding | 2-Hop Acc | 3-Hop Acc | Probe Acc (Best Layer) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 3 | Absolute | 95.0% | 0.0% | 45.0% (L2) |

| Bottleneck | 3 | Absolute | 95.0% | 0.0% | ~45% (L2) |

| Deep-4 | 4 | Absolute | 93.8% | 0.0% | 74.5% (L3) |

| Deep-6 | 6 | Absolute | 93.1% | 0.0% | 88.2% (L5) |

| RoPE | 3 | Relative | 96.25% | 96.56% | 88.5% (L2) |

Side-by-side comparison of all models. The RoPE model stands alone in achieving generalization while maintaining high probe accuracy.

The Optimal Architecture

Based on these results, the ideal model would be:

- Deep RoPE model (6+ layers with rotary embeddings)

- Gets both benefits:

- RoPE for length generalization (96%+ on 3-hop)

- Depth for potentially even clearer internal representations

I haven’t built this yet (production_v6_rope_deep exists but hasn’t been fully evaluated), but the data strongly suggests it would work. The 3-layer RoPE model already matches the 6-layer baseline’s probe accuracy, so a 6-layer RoPE model might achieve even higher clarity while maintaining generalization.

Key Takeaways

1. Position Encoding Matters More Than You Think

I spent weeks testing bottlenecks and depth variations.

A single change to position encoding (absolute → RoPE) solved the problem instantly.

The inductive bias from position encoding dominates architecture choices.

2. Generalization and Internal Clarity Are Different

You can have:

- Clear representations without generalization (6-layer baseline: 88.2% probe, 0.0% OOD)

- Generalization with clear representations (3-layer RoPE: 88.5% probe, 96.56% OOD)

- Poor representations without generalization (3-layer baseline: 45.0% probe, 0.0% OOD)

But you can’t have generalization without the right inductive bias (RoPE). No amount of depth or capacity can overcome the wrong coordinate system.

3. Read Papers on Architectural Components

Papers on RoPE existed. I should have read them earlier.

Understanding why different position encodings exist would have saved weeks of failed experiments.

4. Always Test OOD From Day 1

If I had tested 3-hop generalization on day 1, I would have known immediately that absolute positions were the problem.

Testing only 2-hop accuracy gave me false confidence.

5. Probe Accuracy Is Diagnostic, Not Evaluative

High probe accuracy (88%) doesn’t mean the model will generalize. The 6-layer baseline had 88.2% probe accuracy but 0% generalization.

It tells you the model has structure, but not whether that structure is useful for the task at hand. The structure might be optimized for the training distribution rather than general reasoning.

Use probes to understand what the model learned, not to validate that it learned correctly.

Mistakes I Made

1. Focusing on Model Capacity

Spent 2 weeks testing bottlenecks and depth before trying position encodings.

2. Trusting 2-Hop Accuracy

All my models got 93-96% on 2-hop. This masked the real problem. I should have tested 3-hop generalization from day one.

3. Overinterpreting Probe Results

I thought 88% probe accuracy meant the model “understood” the task. It just meant the model had clear internal representations - but those representations could be optimized for memorization rather than generalization.

Open Questions

1. Would Deep RoPE Be Even Better?

6-layer model with RoPE instead of 3-layer? (production_v6_rope_deep exists but needs full evaluation)

Hypothesis: Would get both 96%+ OOD accuracy AND potentially even clearer internal representations (possibly >90% probe accuracy).

2. What About 4-Hop? 5-Hop?

RoPE solved 3-hop. Does it scale indefinitely?

3. Why Does RoPE Improve Probe Accuracy?

The 3-layer RoPE model matched the 6-layer baseline’s clarity. What’s the mechanism?

4. Does This Apply to Other Reasoning Tasks?

Tested on transitive chains. What about arithmetic? Logic? Graph traversal?

5. Can We Visualize the Difference?

What do the attention patterns look like in RoPE vs absolute position models? This would help explain why RoPE enables generalization - do the attention heads learn different patterns?

Related Reading

Papers I should have read earlier:

- “RoFormer: Enhanced Transformer with Rotary Position Embedding” - Su et al., 2021

- Explains why relative positions help

- Length generalization benefits

- Would have saved me weeks

- “Train Short, Test Long: Attention with Linear Biases Enables Input Length Extrapolation” - Press et al., 2021

- Alternative to RoPE (ALiBi)

- Same core insight about relative positions

Papers that explained my probe results:

- “In-context Learning and Induction Heads” - Olsson et al., 2022

- Pattern matching mechanism

- Why depth alone doesn’t help

- “Probing Classifiers: Promises, Shortcomings, and Advances” - Belinkov, 2022

- What probe accuracy measures

- Why 88% ≠ reasoning

What’s Next

Immediate

- Fully evaluate 6-layer RoPE model (production_v6_rope_deep)

- Test RoPE model on 4-hop, 5-hop chains to find length limits

- Document whether there’s a depth limit even with RoPE

- Compare training efficiency: does RoPE converge faster?

Short-term

- Compare RoPE vs ALiBi vs other relative position encodings

- Test on different reasoning tasks (arithmetic, logic)

- Systematic ablation of RoPE parameters

Long-term

- Understand why RoPE improves internal structure

- Test hybrid approaches (RoPE + explicit memory)

- Scale to larger models

Conclusion

The lesson: Sometimes the answer isn’t in model capacity or training techniques. It’s in the fundamental inductive biases of your architecture.

Position encoding seemed like a minor implementation detail. It turned out to be everything.

When your model fails to generalize, ask:

- What assumptions are baked into the architecture?

- Do these assumptions match the task requirements?

- What if I changed the coordinate system the model uses?

Because sometimes the problem isn’t that your model can’t learn. It’s that you gave it the wrong language to think in.

This is post #2 in my ASI Architect series.

Previous: “GELU vs ReLU at Unconventional Learning Rates”

Next: [Coming soon - testing the limits of RoPE generalization]

Appendix: Experimental Details

Training Configuration

- Optimizer: AdamW with learning rate 3e-4

- Batch size: 64 (baseline), 32 (depth experiments)

- Training steps: 10,000 for all models

- Evaluation: Every 500 steps (baseline) or 200 steps (depth experiments)

- Vocabulary: 32 tokens (A-Z, →, ., Q, ?, special tokens)

- Sequence length: 64 tokens (block_size)

Model Architectures Tested

- Baseline (3-layer): Standard GPT with absolute positional embeddings

- Bottleneck: 3-layer with [256, 128, 256] dimensions

- Deep-4: 4 layers, all 256 dimensions

- Deep-6: 6 layers, all 256 dimensions

- RoPE (3-layer): Same as baseline but with rotary position embeddings

Key Metrics Tracked

- 2-hop accuracy: In-distribution test performance

- 3-hop accuracy: Out-of-distribution generalization test

- Probe accuracy: Linear classifier accuracy on intermediate node prediction

- Training/validation loss: Standard cross-entropy loss

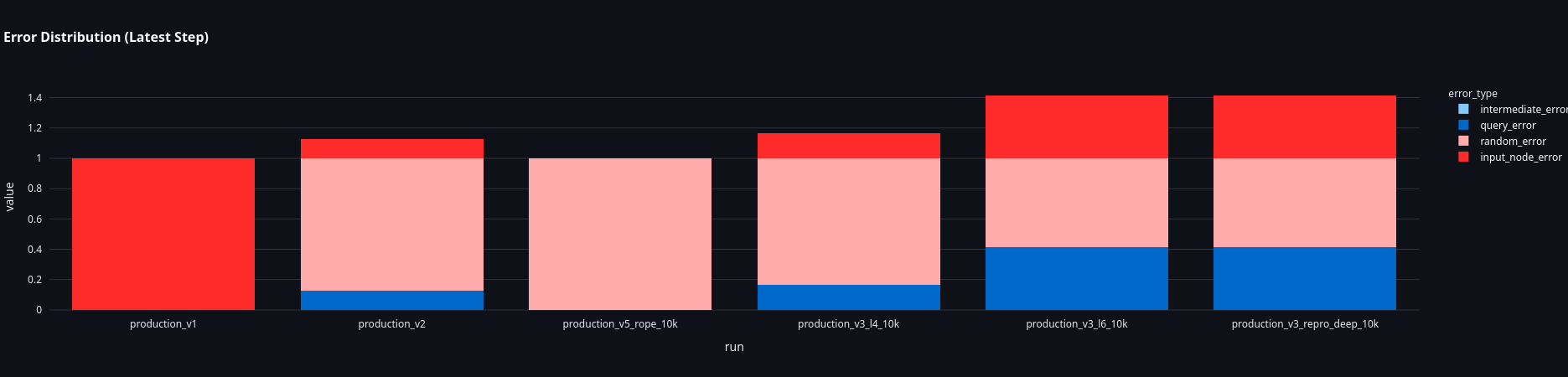

Breakdown of error types across models. This diagnostic information helps understand failure modes - whether models fail on intermediate steps, query parsing, or random guessing.

Breakdown of error types across models. This diagnostic information helps understand failure modes - whether models fail on intermediate steps, query parsing, or random guessing.

Last updated: January 20, 2026

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: